The anatomy of a golf course - fairways

"There must always be an alternative route for everyone, and thought should be required as well as mechanical skill, and above all it should never be hopeless for the duffer, nor fail to concern and interest the expert"

"There must always be an alternative route for everyone, and thought should be required as well as mechanical skill, and above all it should never be hopeless for the duffer, nor fail to concern and interest the expert"

Bobby Jones, Course Designer, Augusta National

The fairway was originally a description of the desirable area within which to land the ball. The original links golf courses wouldn't have had clear cut fairways that would be recognised by today's manicured standards, but the term originates from the fairer ground created by continual grazing by the animals that were kept on or naturally inhabited the links land, and it is these areas that will have defined where best to place bunkers near, or greens upon.

Structure

The fairway consists of two main parts, the fringe which links the fairway with the green, and the landing zone(s) which are designed to receive a ball and set up a shot to a second landing zone or to the green. The size and shape of a fairway is usually governed by its surroundings, but should also provide strategic options as to how the hole should be played by the approaching golfer.

The fringe is the section of the fairway, typically forming an apron shape at the front, that links the green and the fairway together. The fringe is usually cut at an interim depth to the shorter green and the longer fairway, but all should allow for a ball to roll across the surface. The fringe has become a fashionable element of the golf course, as the nature of the shorter cut turf allows the maintenance teams to create attractive cross hatch patterns.

The fringe can stretch out and around the green to encompass approximately the last fifty yards of the hole, creating great short game interest. A golfer missing the surface, or intentionally laying up short, has the option of playing a variety of shots, including bump and runs, flop shots, or even putting. Hollows that were once easily attacked with a lob wedge can now be putt through, adding another decision making point for the golfer to consider.

Fringes can provide aesthetic interest, but in the guise of a short mown hollow they are now considered an equal or even greater challenge than the bunker, due to their unpredictable nature. The picture right shows an example of a large fringe area. Conversely, some designers and tournament organisers prefer to remove a lot of the fringe to force the golfer to play chip shots from relatively thick rough if they miss the green, and this can also provide a stiff challenge.

Fringes can provide aesthetic interest, but in the guise of a short mown hollow they are now considered an equal or even greater challenge than the bunker, due to their unpredictable nature. The picture right shows an example of a large fringe area. Conversely, some designers and tournament organisers prefer to remove a lot of the fringe to force the golfer to play chip shots from relatively thick rough if they miss the green, and this can also provide a stiff challenge.

The landing zone is the area of the fairway that has been designed to attract a high percentage of tee shots. I try to create slightly larger, flatter (where possible) areas in the fairway at the point where the majority of balls are likely to come to rest. If the golfer finds this area, they will then be rewarded with a more advantageous position from which to attempt their approach shot.

When a series of landing zones are created, the designer can create vantage points within the fairway which are smaller to hit, but gain higher reward, or bluff the golfer into thinking that they should play towards a larger, more visible landing zone that has a tighter angle of approach for example.

On new sites, these areas should be sought out in the pre-existing topography, and modified as little as possible, in order to limit the unnatural feel that can be created by too much land movement. Where there is no topographic interest, landing zones should be formed with a subtlety that makes them look natural to the untrained eye.

Multiple landing zones can be created if the situation calls for a split fairway, or when there is enough space for the hole to be played in different ways. I have also been exploring the merits of staggered landing zones on longer par 4s and par 5s. The issue being that, whilst the designer at present caters purely for the tee shot of players of differing abilities, by staggering the teeing grounds in order for all golfers to be able to find the same landing zone, the approach shot will still be vastly in favour of the longer hitters versus shorter hitters.

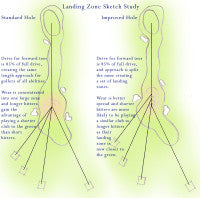

I have completed a sketch study to show how shorter hitters may be catered for by using a set of staggered landing zones and teeing zones, meaning that on approach, the shorter hitter should be nearer the target than the longer hitter, balancing out both shots for all levels of golfer. Figure one shows two similar holes. The standard hole shows tees playing to one landing zone, whereas the improved hole shows tees playing to four staggered landing zones.

I have completed a sketch study to show how shorter hitters may be catered for by using a set of staggered landing zones and teeing zones, meaning that on approach, the shorter hitter should be nearer the target than the longer hitter, balancing out both shots for all levels of golfer. Figure one shows two similar holes. The standard hole shows tees playing to one landing zone, whereas the improved hole shows tees playing to four staggered landing zones.

The size and shape of a fairway will vary greatly depending on the available space for each hole. With ample room at Augusta, for example, Alister MacKenzie and Bobby Jones's original design idea was to cut out large paths through the trees of the pre-existing orchard and mow almost everything in between as fairway, giving the golfer options on every tee. Jones's words from the Golfer's Year Book reiterate this; "There must always be an alternative route for everyone, and thought should be required as well as mechanical skill, and above all it should never be hopeless for the duffer, nor fail to concern and interest the expert".

However, Augusta National currently has a more considerable rough line and longer and tighter fairways, potentially losing some of the design's integrity. Tighter courses may not afford such luxury, but it is usually still possible to create a varied challenge with the correct placement of hazards. A fairway which is twisted on a diagonal can be a successful way to create interest or, more subtly, creating or utilising a pre-existing roll or plateau within the fairway line can set up an advantageous and disadvantageous position in relation to the green.

The golf course architect looks to create a playing area wide enough for balls to find a good selection of landing points, which will help to spread wear whilst also creating a realistic challenge. Fairways that include steep slopes can sometimes struggle, with many balls landing in a relatively small area leading to wear points which, after a playing season, could be littered with divots and bad lies. The architect should look to avoid these issues at the design stage by making some subtle adjustments that can spread the wear of these problem areas.

In order to tie the golf hole together, the fairway line should generally look to pass through the landing zone incorporating the bunkers within its skirts, tempting the golfer with the preferred landing zone between these points. This should be wide enough to conceivably land a ball struck at full length with a driver in most cases, equating to a landing zone of between 20-40 yards wide, although some courses can include much wider fairways.

In order to tie the golf hole together, the fairway line should generally look to pass through the landing zone incorporating the bunkers within its skirts, tempting the golfer with the preferred landing zone between these points. This should be wide enough to conceivably land a ball struck at full length with a driver in most cases, equating to a landing zone of between 20-40 yards wide, although some courses can include much wider fairways.

Fairways are time consuming elements of golf course maintenance, and the acreage of the eighteen fairways within a typical course directly reflects the amount of time taken to maintain them. This has meant that some courses have greatly reduced the width and, in some cases, the length of fairways in order to cut down on the man hours taken to maintain them, adding to the likelihood of the average width stated above.

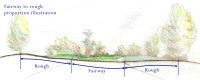

The overall course size also adds an upper limit to the likely width of a fairway as the hole should, at all costs, look to integrate with its surroundings. If it is hemmed in on both sides by other holes, then the fairway, visually, should look to fill approximately a third of the available space, to allow for clear separation between one hole and the next (see figure two below).

Placement

When designing a golf hole on paper, I look to add the fairway line last. This is the element of the hole which draws the other elements of the hole together. The playing area will typically expand around the landing zone, and contract in the areas where fewer balls are likely to come to rest. It will wind through bunker complexes and wrap around the green, incorporating some run off areas that may help to create greenside playing and aesthetic interest.

The levels of the fairway have to be shaped to allow for shots to be played from it, to appeal enough for shots to be played at it, for it to be aesthetically pleasing and visible for the approaching golfer, and to tell a story, or sometimes sell a story about how the golf hole should be played. Without the fairway as the central focal point of the golf hole, there would be no hierarchy of targets to be aimed at, the hazards would simply be floating in an empty field, and the hole would struggle to make sense.

The fairway's relationship with the rough is also very close. The designer's decision on where the fairway line is placed is as much about the importance of a good lie as a bad lie, because the fairway line will obviously always determine the rough line.

In a lot of cases in the modern game, a semi rough line is cut for the first few metres into the rough to aid golfers whose balls trickle off the fairway. Past this point the challenge for the golfer increases. A shot played into the rough should lessen the available options to the golfer. The ball is less likely to spin from a lie in longer grass, and may be more impeded by obstacles such as trees or a bunker complex within the line of sight to the green, and the shot will have to be played stronger and truer to find a similar length and accuracy to those shots played out of the fairway. It is, therefore, an important element within the strategy of a golf hole.

The conscious designer will look to create a naturally shaped rough line which generally follows the contours of the hole and interjects the playing line at points that will challenge the golfer. For instance, the fairway may be a diagonal form which tests the golfer from the tee to carry as much of the rough line in order to progress down the fairway, knowing that, if the first bounce finds the rough line, it is likely to affect the final length of the drive.

Deep rough lines generally tend to correlate with the semi rough and rough lines, but shouldn't interject with the playing line unless the hole is a relatively sharp dogleg, or there is a forced carry. Deep rough, if maintained and placed correctly, can also add to the aesthetic complexity of a golf course, adding depth of textures and colours. This feature should be used rarely as a hazard, as balls can be easily lost in thick rough lines resulting in slow play. Yet, if placed well away from a target line, but still at a point which is clearly visible, can add much to the aesthetic appeal of a golf course.

Summary

I look to create fairways that link with the other elements of a golf hole to provide a varied challenge throughout the course of a round. The fairway should balance and reflect all other elements of the course, either pre-existing or designed,

and should create a path for the golfer to aim towards and play successfully through, rewarding them as they find the right points within the wider hole.

and should create a path for the golfer to aim towards and play successfully through, rewarding them as they find the right points within the wider hole.

This article has considered the fairway as the lynch pin of the other elements of the golf hole, and has given an insight into the elements that I look to include when successfully designing the fairway line into a golf hole.

In this series Andy Watson has picked the four major elements of a golf course and dissected them to provide an insight into the fundamentals of an architect's approach to designing a golf course. We hope you have found all four articles interesting to read. If you are interested in Andy's work, or are interested in working with him, you can follow him on twitter @AWGolfDesign, be a 'fan' of his facebook page (search for Andy Watson Golf Design), or visit the website www.andywatsongolfdesign.co.uk.

Picture captions:

1. 15th fairway at West Hill Golf Club

2.Tom Doak's design at Renaissance touches on the traits of links courses by providing extensive fringe areas, creating some interesting short game challenges

3. Figure one: Sketch study showing how staggered landing zones can improve the fairness of a hole.

4. Figure two: Illustration showing a well proportioned fairway to rough ratio.