Earthworms: Friend or Foe?

Earthworms: Friend or Foe?

By Mark Bartlett

Horticulturalists the world over have been encouraging earthworms in the soil for years, but the turfgrass industry has always seen them as a pest. Why is it that groundsman hate and fear earthworms so much? Should they really be that concerned about all of them? How can they control them? Cranfield Centre for Sports Surfaces has taken on the challenge to answer these questions.

Earthworm Biology

Earthworms eat soil, and lots of it. They can eat up to 30 times their own body weight every day which passes out of the other end as fertile, well structured aggregates. There are normally about 300 earthworms below a square metre of turf, and the burrows that earthworms create and live in improve the drainage of soil. Earthworms also eat thatch and other organic material in the soil so they can reduce thatch build up. Earthworms help to complete nutrient cycles in the soil, reducing the need for inorganic fertilisers. A healthy earthworm population has the same effect as adding 100 kg of nitrogen fertiliser per hectare every year because they free nutrients from the soil.

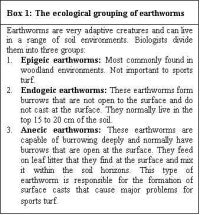

Not all earthworms behave the same way, only deep burrowers earthworms are a pest to turfgrass (see Box 1) because of the casts that they leave on the playing surface (Figure 2). There are 25 different species of earthworm found in the United Kingdom, but only three are deep burrowers causing this problem, the most common is Lumbricus terrestris (Figure 1). Non-surface casting earthworms are beneficial for turf growth, being responsible for the majority of the nutrient recycling and thatch breakdown.

Earthworm Habitats

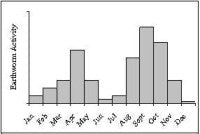

Earthworms can survive in a wide range of conditions, but most earthworm activity is dependent on the quality of food available and the season. Deep burrowing earthworms will thrive where clippings are not boxed since food is always available. During the year when soil temperatures are at their lowest and highest earthworms go into a form of hibernation where they do not eat and can not move. This is why there are more problems with earthworms in the spring and autumn (see Figure 3). The soil pH affects where earthworms are found and in strongly acid or alkaline soils earthworms are rarely seen (pH less than 4.5 or greater than 8). The soil texture will also affect the number of earthworms found; they prefer clay soils and are less frequently found in sandy soils.

|

|

| figure 1. | figure 2. |

Earthworms in Turfgrass

Farmers encourage deep burrowing earthworms to thrive in their fields because of all the nutrient benefits they give, but casts on the surface of turf cause groundsmen several problems. Deep burrowing earthworms generate casts that spoil the appearance of the turf surface that customers have paid to play on (Figure 2). More than this, if casts are then pushed across the surface by mowers or trodden underfoot then they can create patches of turf that are hard to revive and can also cause problems with drainage. On sandy soils this can also blunt mower blades. Another problem is that deep burrowing earthworms can move weed seeds from within the soil to the surface where they are able to germinate. Earthworm casts provide ideal conditions for germination; they are loosely packed, moist and full of nutrients. Even if the seeds are not in the soil, the earthworm casts provide a perfect tilth for wind blown weed seeds to germinate.

|

| Figure 3 : A graph of annual earthworm activity on a golf course |

Control of Earthworms

Historically, earthworms have been controlled chemically, killing all earthworms in the turf. The most widely used chemical was chlordane, an organochloride, now banned due to it's wide ranging toxic effects and persistence in the environment. Other chemicals such as benomyl, carbendazium, thiabendazole and thiophanate-methyl (all of which are primarily fungicides) have an effect on earthworm populations. Research has shown that thiophanate-methyl is the most effective at reducing casting. All these fungicides are considerably less effective at earthworm control than chlordane.

Some groundsmen use a different approach, trying to make the soil unsuitable for earthworms. This is achieved in two ways: the available food is reduced, by boxing grass clippings; and the soil is acidified using sulphur-based fertilizer thus lowering pH. The disadvantage of this approach is that soil unsuitable for earthworms is also unsuitable for turf, which can struggle to grow. Prior to the widespread use of chlordane, one way earthworms were controlled was using chemicals that forced the deep burrowing earthworms to the surface. The chemical irritates the earthworms which come up to the surface. The draw back with this method is that the earthworms then need to be collected and disposed of.

The Solution?

Groundsmen are always trying to strike a balance between the positive and negative effects of earthworms. Everybody wants the increased aeration, drainage and nutrient cycling advantages of having the earthworms present, but nobody wants the problems associated with casting.

Soil scientists at the Cranfield Centre for Sports Surfaces and the National Soil Resources Institute have been researching this problem, by trying to link all of the pieces of the puzzle. Focusing on golf courses they are measuring the size of the casting problem, working out what species are causing the damage and why they are there. Once these pieces are fitted together it should be clearer how the deep burrowers can be controlled and still maintain the advantages from the non-surface casters. Watch this space!

About the Author:

Mark Bartlett is currently studying for a PhD in Soil Ecology at Cranfield Centre for Sports Surfaces, part of Cranfield University at Silsoe, under the supervision of Professors Karl Ritz, Jim Harris and Dr Iain James. Any enquires should be sent to m.d.bartlett.s04@cranfield.ac.uk or Cranfield University at Silsoe, Barton Road, Silsoe, Bedfordshire. MK45 4DT.

Cranfield Centre for Sports Surfaces is a centre for research and training expertise based at Cranfield University at Silsoe. It provides the MSc Sports Surface Technology degree, unique in Europe for the advanced education of industry professionals. It is also a centre for excellence in both doctoral and commercial research, working with industry bodies and the UK government to advance knowledge, and to develop safe, sustainable sports surfaces in all environments. More details are at our website www.silsoe.cranfield.ac.uk/ccss.

The National Soil Resources Institute was established in 2001 to create a unified institute with the necessary scientific expertise and research capability to focus on the long-term development of the sustainable management of soil and land resources, both in the UK and around the world. Further information about NSRI is available at: www.silsoe.cranfield.ac.uk/nsri/